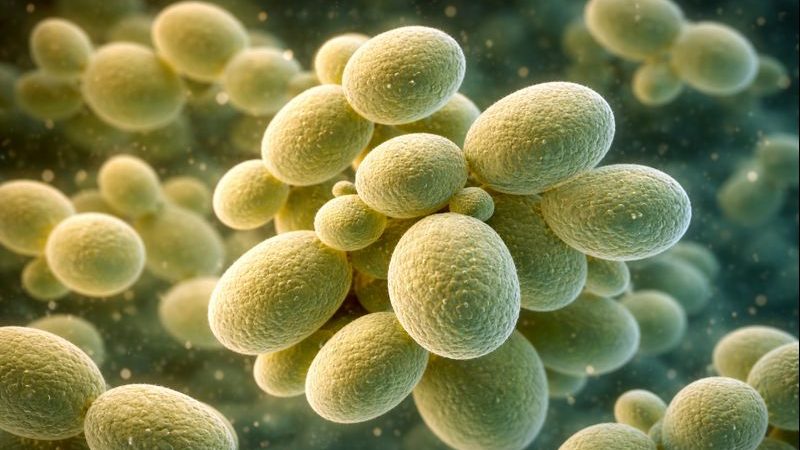

What Saccharomyces cerevisiae is to bakers, Komagataella phaffii is to biotechnologists – an important tool for the production of key chemical compounds. A research team led by acib, with participation from graz university of technology and bisy Gmbh, has systematically investigated the behavior of the important industrial yeast Komagataella phaffii after use for the first time. The results are a triple success: the yeast survives poorly in the environment and is therefore an ideal cell type for industrial processes. In addition, it can be inactivated with significantly less energy than previously assumed. Above all, however, its biomass can be used as a valuable residual material for the production of biogas, which in turn strengthens the circular economy.

Industrial biotechnology is a central pillar for a sustainable future. It uses microorganisms such as yeasts to produce drugs, fine chemicals, and proteins. One of the world’s most important yeasts for these processes is Komagataella phaffii (also known as Pichia pastoris). But what happens to the huge quantities of yeast cells after they have fulfilled their purpose? How can their safety be ensured and the resulting biomass be put to good use?

In a comprehensive study, the research team led by Sarah Gangl (acib GmbH) and Anton Glieder (Graz University of Technology, bisy GmbH) investigated three key aspects that are of utmost relevance to the industry:

- Survival of cells in nature: What happens if the yeast accidentally enters the environment? Experiments in simulated soil and water environments (microcosms) showed a clear picture: The number of viable yeast cells decreased rapidly. It was unable to compete with natural microorganisms. Genetic mixing (mating) did not occur under these conditions either. These results are a reassuring confirmation of the high safety profile of this industrial organism.

- Energy-efficient inactivation: Until now, yeast cells have often been killed at high temperatures (121 °C, autoclaving), which is very energy-intensive. The study demonstrated that K. phaffii reacts highly sensitively even at significantly lower temperatures. Heating to 70 °C for a few seconds is sufficient to completely inactivate the cells. This finding opens up avenues for significantly more energy- and cost-efficient processes in industry.

-

From waste to value creation:Perhaps the most exciting finding lies in the utilization of the residual biomass. Instead of disposing of it, the yeast was used in an anaerobic fermentation process to produce biogas. The result: the protein-rich yeast biomass is an excellent substrate and can even increase methane yield in biogas plants. This turns a waste product into a valuable raw material for renewable energy and makes the vision of a circular economy a reality.

“Our fundamental questions about the biology of K. phaffii always had industrial applications in mind,” explains Prof. Dr. Anton Glieder from Graz University of Technology and bisy GmbH, one of the lead authors of the study. “We wanted to know how we could make processes not only more efficient, but also more sustainable and safer. The results show that ecological responsibility and economic benefits can complement each other perfectly.”

The results of the publication directly contribute to key societal goals:

- Resource efficiency: Energy-saving inactivation methods reduce the CO₂ footprint of biotechnological production.

- Circular economy: The conversion of biomass waste into biogas closes material cycles and promotes a sustainable bioeconomy.

- Responsible innovation: The sound data on biosafety creates trust and a solid basis for the safe handling of biotechnological production organisms.